Between 1886 and 1900, a Mohawk Valley art teacher named Rufus Grider, sketched and painted current scenes as well as historical reconstructions of the Mohawk Valley. Some of his watercolors are delightful and many are fully realized works of great delicacy and charm. Others are monotints. His paintings and drawing usually have handwritten notes pointing out features and directions. Grider interviewed old-timers to learn about details of landscape or of Revolutionary War-era structures no longer existing. The art works not infrequently contain signed statements from his informants, often in a shaky hand, testifying to their faithfulness.

All these paintings and drawing are from the NYS Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections. The Rufus Alexander Grider collection is in nine volumes. These photographic copies were provided to me by Craig Williams of the NYS Museum. The collection includes more than a thousand items. My original intention was to document changes in land use but there is much more to see. Art can be an unreliable witness as the artist may include or leave out features he feels are un-aesthetic some of which may be of considerable interest to future viewers. The testimonials from his aged informants provide a little reassurance.

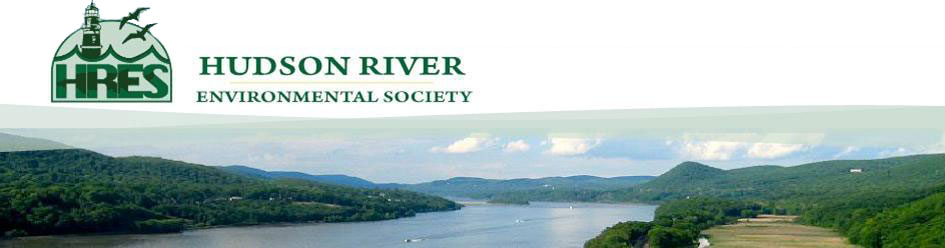

Schoharie Creek at Middleburgh. Collection VC22932; Volume 8, Item # 43

This is among my favorites. It doesn’t indicate much about land use but it’s both very pretty and quite similar to the current scene. Grider moved to Canajoharie with two daughters (considerably older than these girls) after the death of his wife. Elsewhere Grider notes that the Schoharie here is usually very placid and safe for unsupervised children to go boating.

The Arkell Museum in Canajoharie will be displaying many of these images, as well as others, until August 14, 2011. Anyone interested in Mohawk Valley history, and in local art, would be well advised to see the exhibit.

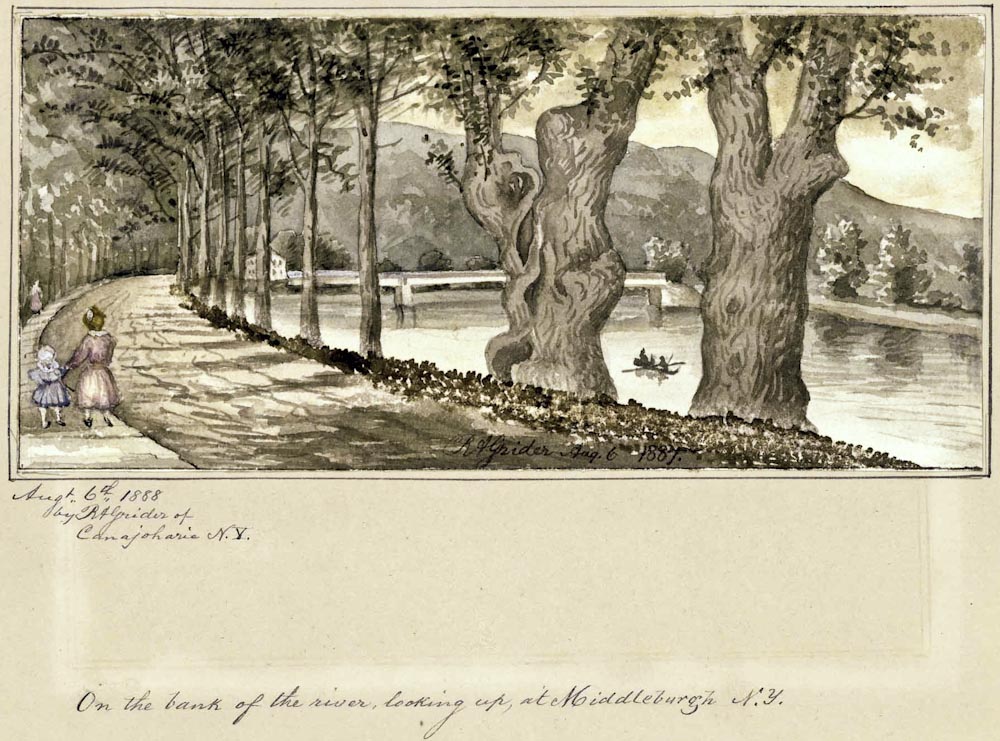

Collection VC22932; Volume 8, Item # 44

This is possibly J. M. Scribner’s paper mill, one mile north of Middleburgh. The history of paper manufacture in New York deserves a great deal of attention. The Hudson/Mohawk Valley was the scene of important technical innovations. The Hudson Valley was an early center of straw paper manufacture. Rye straw could be grown on marginal lands and the paper manufactories provided a ready market. Straw paper canoes were made in Troy and straw paper-core railroad car wheels made in Hudson cushioned Pullman cars. Newspapers were printed on straw paper but its siliceous nature damaged typeface. Little Falls saw some early, but unsuccessful, attempts to make paper partly from wood pulp.

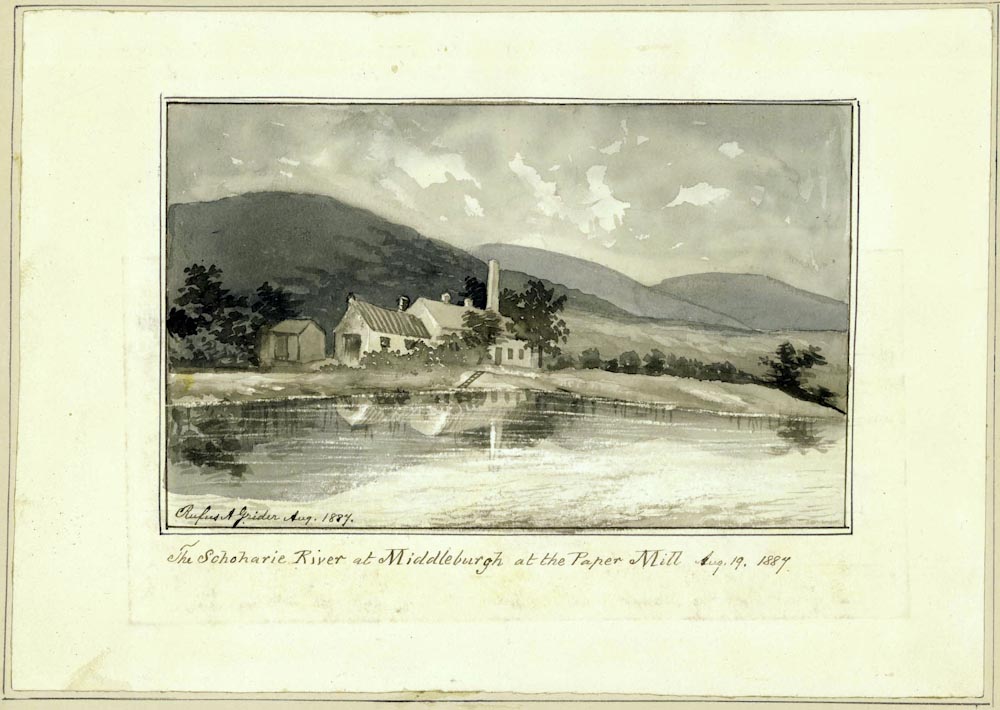

Collection VC22932; Volume 8, Item # 18

The steep hills near Schoharie Village were deforested, perhaps under cultivation but more likely in pasture. The hills in the background are now almost entirely wooded. Grider found the Schoharie Valley to be both beautiful and historically interesting. My attempt to replicate this scene with photography was thwarted by too many trees.

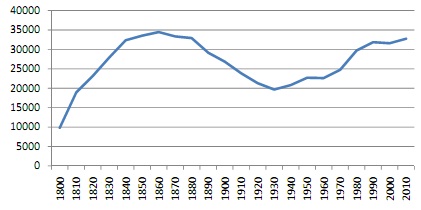

The population of Schoharie County peaked in the 1860 census.

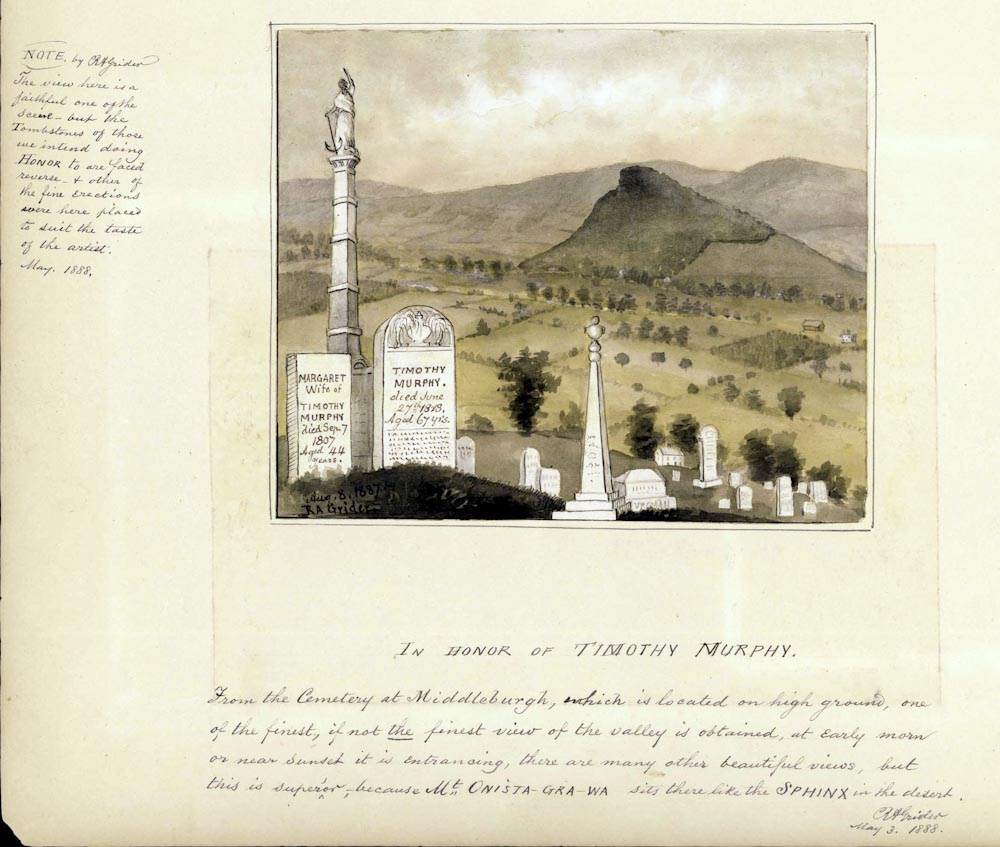

Collection VC22932; Volume 8, Item # 46

Vromans Nose (“Mt Onista-Gra-Wa”) is the steep hill in the background. Timothy Murphy occupies one of the four niches at the Saratoga Battlefield Monument. He is credited with mortally wounding British Brigadier General Simon Fraser with a shot from his Pennsylvania rife at 300 yards. Fraser’ removal was disastrous for the British. The Patriot victory at Saratoga in 1777 was a turning point in the Revolution.

Jeptha Simms’ History of Schoharie County (1845) dwells at some length on the elopement of 29 year old Timothy Murphy and Margaret Feeck, 17 in the dangerous war year of 1780. Margaret was then living with her parents in Upper Fort at Middleburgh and Timothy was stationed a few miles north at Middle Fort in Schoharie. Women who knew her described her as tall, slim, unlettered, fair complexioned, possessing a neatly turned ankle, but with, “altogether too prominent a nasal organ to grace the visage of a perfect beauty.” Timothy was muscular, illiterate, shorter than Margaret, “passionate, and often rough-tongued; but was warm-hearted and ardent in his attachment, and proved himself a kind and indulgent husband, an obliging neighbor and worthy citizen.” He was also a man of renown for his exploits at Saratoga. However, Margaret’s father John, a prosperous farmer, doubted Timothy’s prospects. Margaret sole away under pretext to meet Timothy and they were married. Grider has an image of that romantic event. After a month of difficulty the family accepted Timothy who eventually inherited the considerable Feeck property and lies today in Middleburgh. An octogenarian daughter of Margaret and Timothy helped Grider with details about Upper Fort.

Grider reversed the position of the tombs for artistic effect. Trees in the cemetery obscure the view of the valley at the immediate site of the grave stones.

Part of the inscription on Timothy’s tomb, illegible in Grider’s rendering, reads,: “Sprang from his half drawn furrow as the cry of threaten’d liberty came thrilling by” was a common post-Revolutionary trope. It refers to the Roman Cincinnatus who, in time of crisis, left his plow to assume his civic duty (as dictator) and then, on passing of the crisis, returned to his labors. Washington is often depicted as Cincinnatus.

This scene was photographed in the Middleburgh Cemetery a short distance below the tombs of Margaret and Timothy Murphy. Look at Grider’s “In Honor of Timothy Murphy” and see the right side of the Nose largely cleared and cleared lands climbing up the hills behind the Nose. Grider shows a patchwork of field stretching across the valley up to the river up to Schoharie Creek. The Creek, in the painting, is suggested by parallel lines of trees. In the late 19th Century virtually all of New York State was either in field or pasture. Only the rugged Catskills and Adirondacks were relatively free from agriculture, although not from timber and bark harvest. Now, the Nose is entirely wooded and the hills in the background are almost entirely wooded. Any existing valley patchwork of farms is hidden behind tall trees.

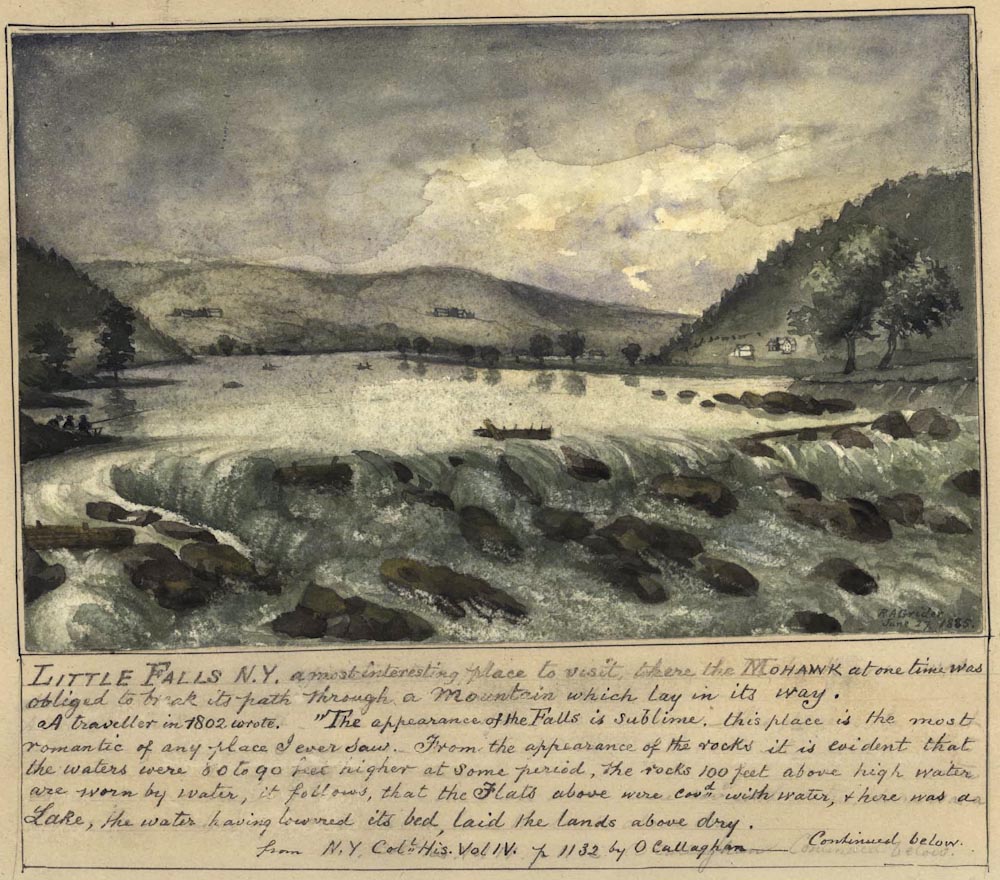

Collection VC22932; Volume 3, Item # 59.

The 1802 quote on Grider’s image of Little Falls is interesting from the standpoint of geological awareness on the part of the Rev. John Taylor, a missionary. Grider’s citation is wrong; this quote appears in Volume 3. Taylor’s full text is:

“Upon the whole, this place is the most romantic of any I ever saw; and the objects are such as to excite sublime ideas in a reflecting mind. From the appearance of the rocks, and fragments of rocks where the town is built, it is, I think, demonstrably evident, that the waters of the Mohawk, in passing over that fall, were 80 or 90 feet higher in some early period than they are now. Ye Rocks even an hundred feet perpendicular above ye present high water mark, are worn in the same manner as those over which ye river passes. The rocks are not only worn by the descent of the water, but in the flat rocks are many round holes worn by the whirling of stones — some even 5 feet deep and 20 inches over. If these effects were produced by the water, as l have no doubt they were, then it follows as a necessary consequence, that the flats above, and all the low lands for considerable extent of country, were covered with water, and that here was a lake — but the water having lowered its bed, laid the lands above dry.”

From Journal of Rev. John Taylor’s Missionary Tour Through The Mohawk and Black River Countries in 1802

Documentary History of New York, vol 3, pp 1131-1132

Taylor is probably referring to the potholes now to be seen (below) on Moss Island near Lock 17.

The outflow of the prehistoric Iro-Mohawk River caused the tremendous turbulence that whirled rocks around grinding into the bedrock here and most famously at Cohoes Falls. The famous Cohoes Mastodon was discovered in a huge pothole.

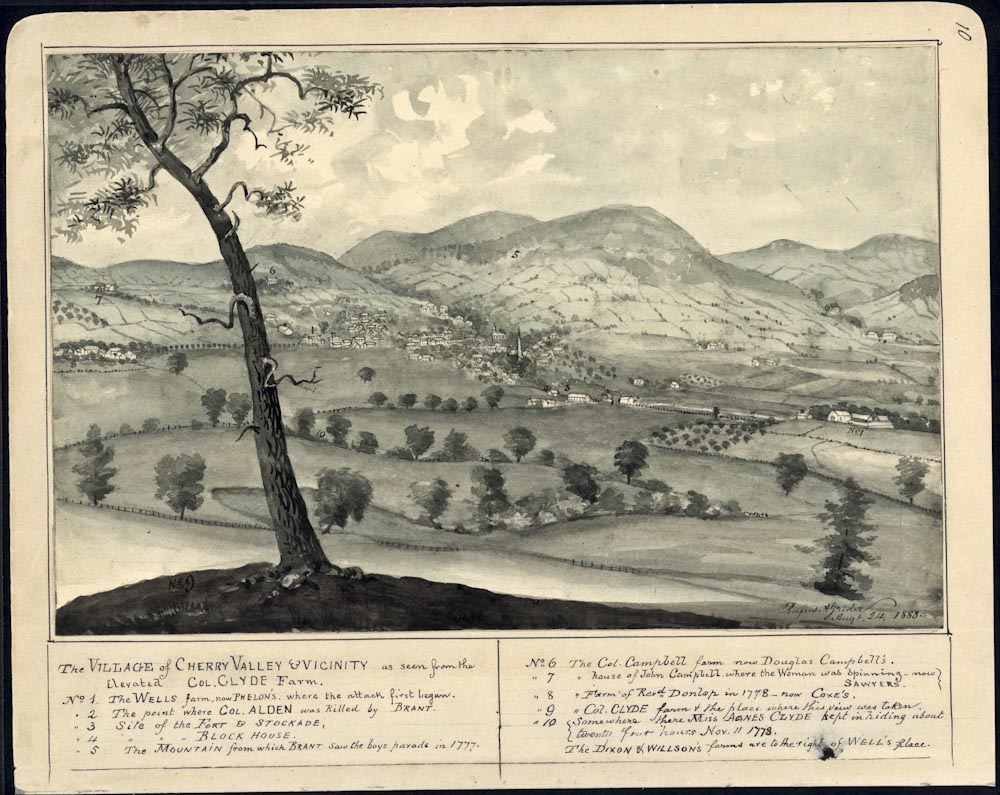

Collection VC22932; Volume 3, Item # 10.

Contemporary view of Cherry Valley from Col. Clyde’s farm. Grider has a number of images from Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary Cherry Valley. His small and charming village was the scene of a horrible massacre in 1778.

Modern view of Cherry Valley from below Col. Clyde’s farm. Only the lower slopes of the hills are now cleared.

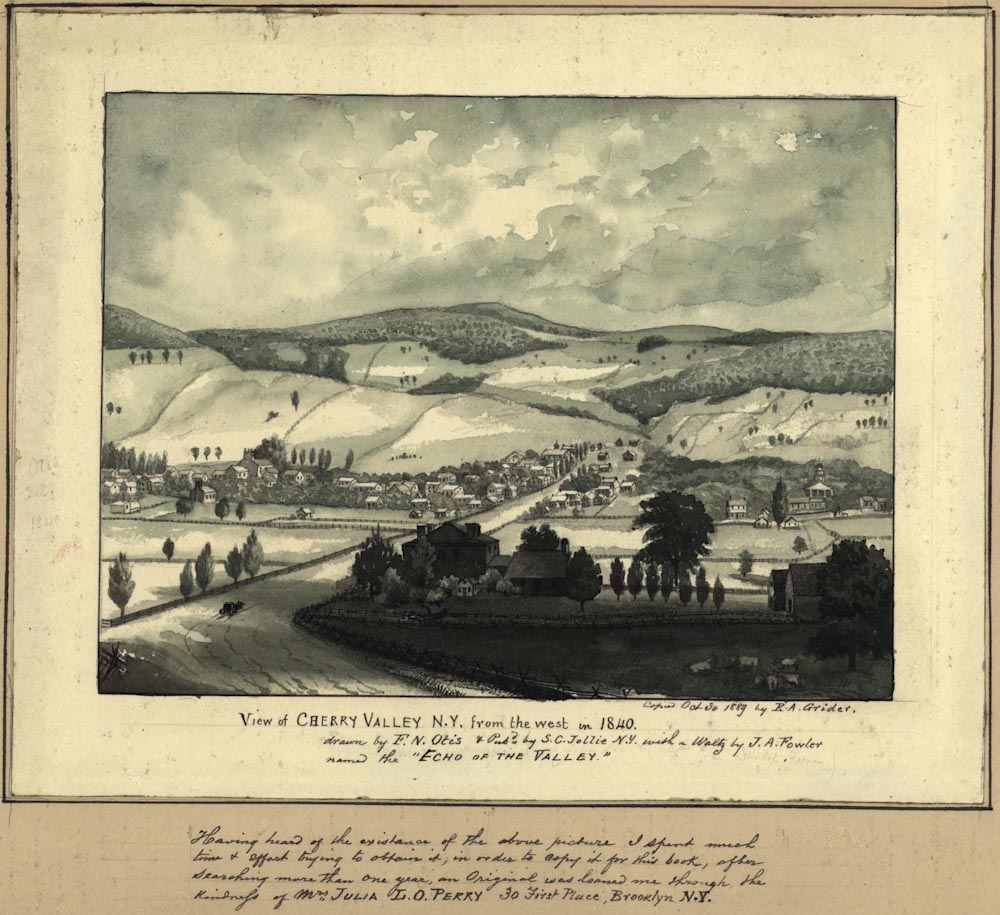

Collection VC22932; Volume 3, Item # 93.

By 1840, in Grider’s copy of an older picture, cleared fields went up high on steep hills. This was probably mostly pasture. Fences line the road and separate the fields. It looks prosperous. This view is from the same general direction as the earlier one. The church, Presbyterian, near the left margin was built in 1828 and replaced by the present edifice in 1873. It claims to be the oldest English speaking church west of the Hudson.

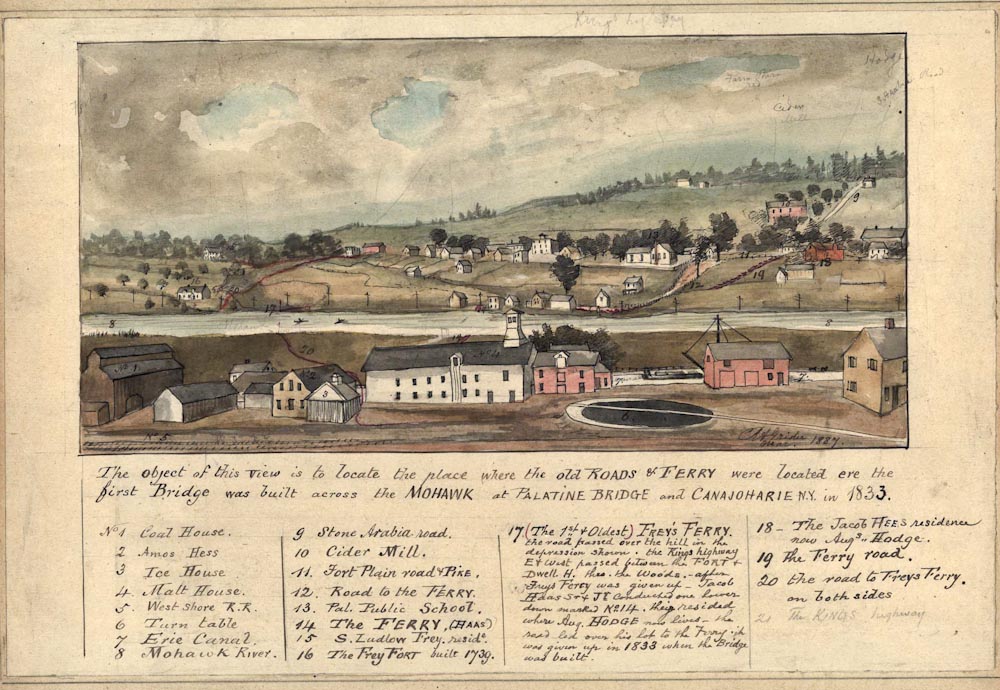

Collection VC22932; Volume 1, Item # 99.

This heavily annotated view of Palatine Bridge and Canajoharie shows Grider’s colorful research for 1833. Despite the detail and care of this lovely sketch, Grider penciled on notes. Does it depict a line of telegraph poles on the far side of the river? Samuel Morse patented his telegraph in 1837. Palatine Bridge, on the far side, is now more treed. Now, the canal is not separated from the Mohawk.

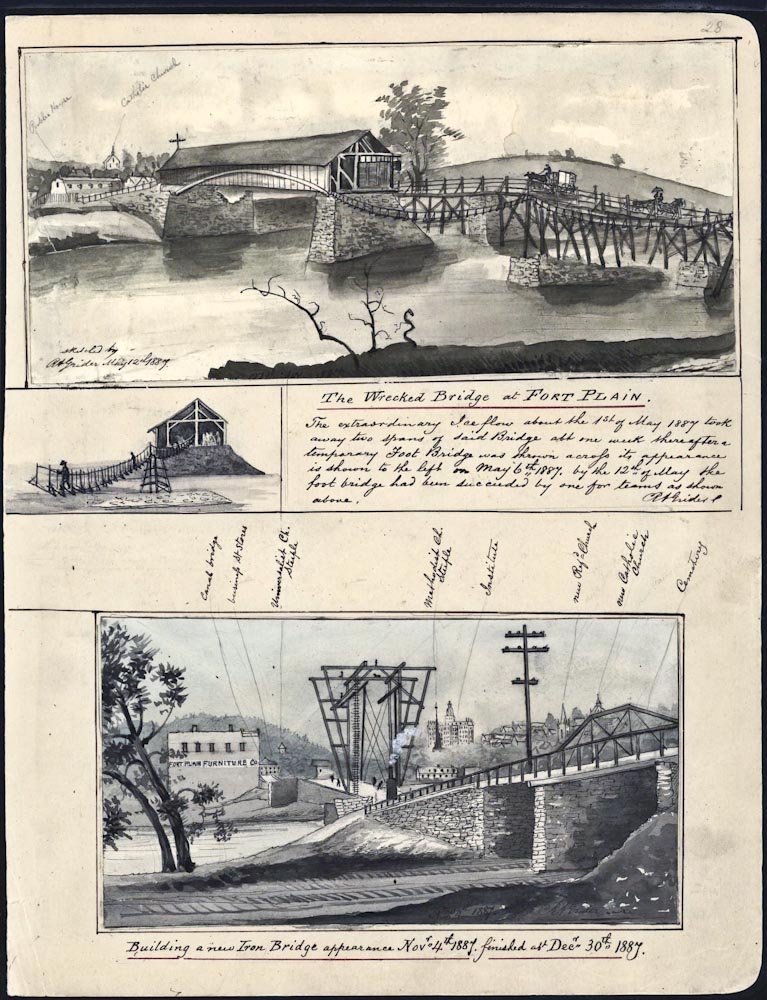

Collection VC22932; Volume 2, Item # 28.

Fort Plain looks like quite the big city here. Note the smoke from a steam engine being used in the construction of the new bridge.

Fort Plain today.

Grider says the bridge at Fort Plain was wrecked by ice on May 1, 1887. Builders of the Barge Canal (completed 1918) were also concerned about floods and ice. The lock structures here at Fort Plan are elevated and rounded to deflect ice.

The large iron structure in the background is a “moveable dam” opened to let water freely pass during the non-navigation season. During navigation season the plates are lowered to control the river’s elevation.

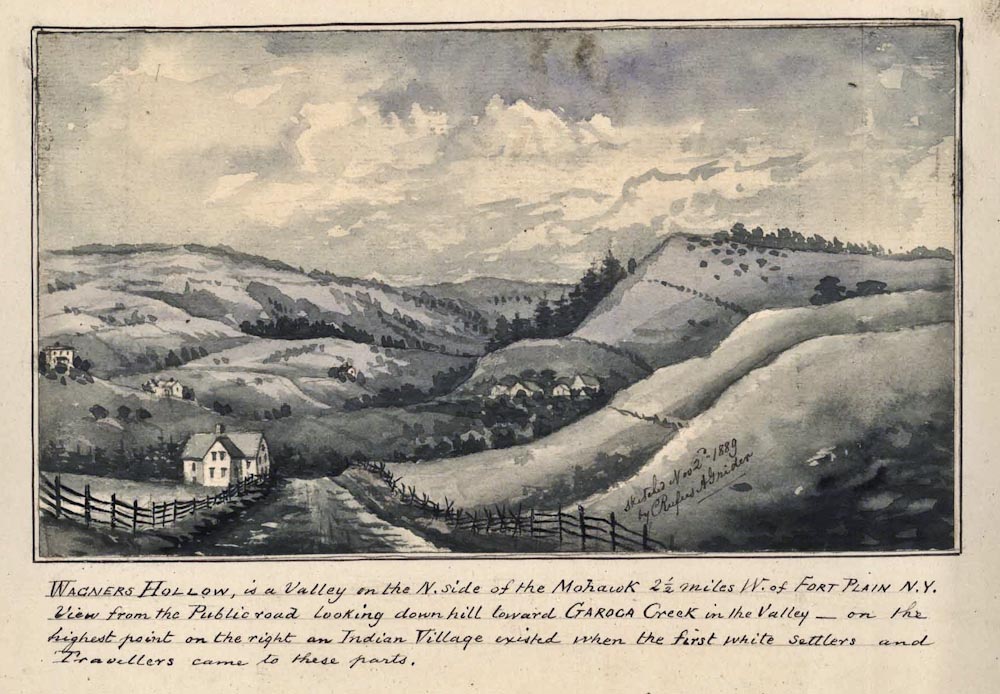

Collection VC22932; Volume 3, Item # 64.

Grider’s note refers to a former Indian Village. He was very interested in Indians and has many images of Indian artifacts but very few of living Indians. The Grider archive collection includes newspaper clippings, some quite long; images from other artists; and lengthy handwritten essays. There is a wealth of information here.

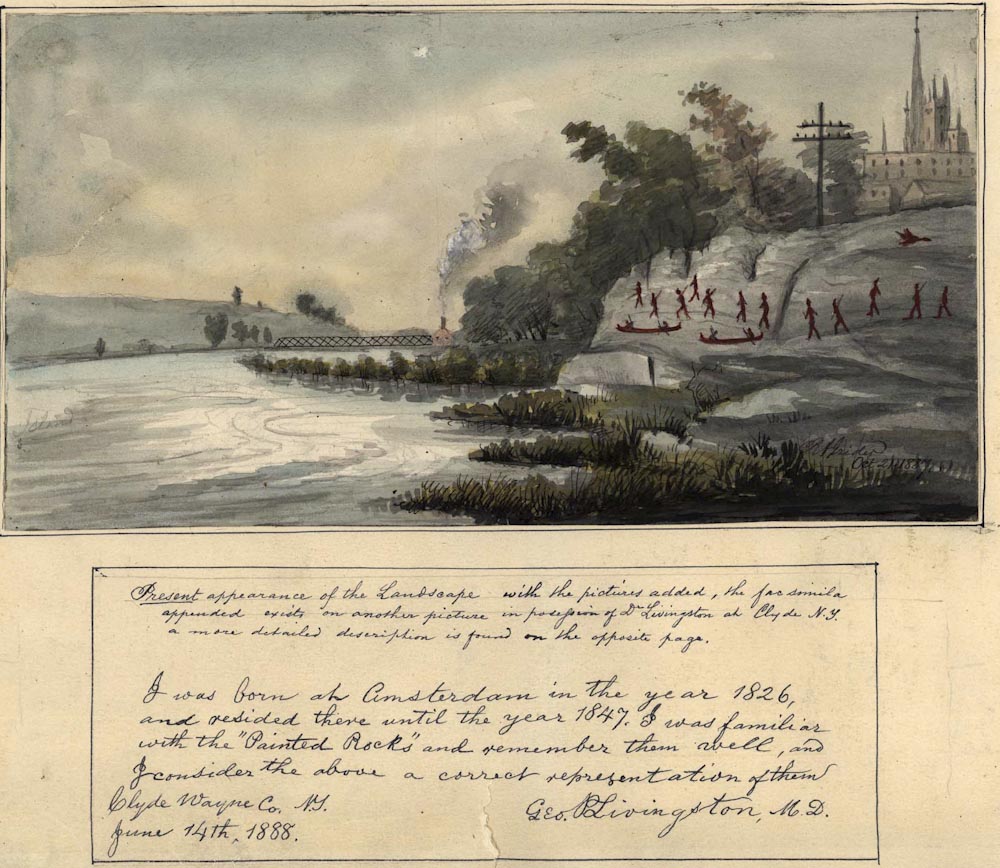

Collection VC22932; Volume 2, Item # 5.

This painted rock in Amsterdam had faded away by Grider’s time. The image shows where it was in the contemporary context. Grider has another version of this scene set in times before the intrusion of the modern city. Note the testimonial from George Livingston, M.D.

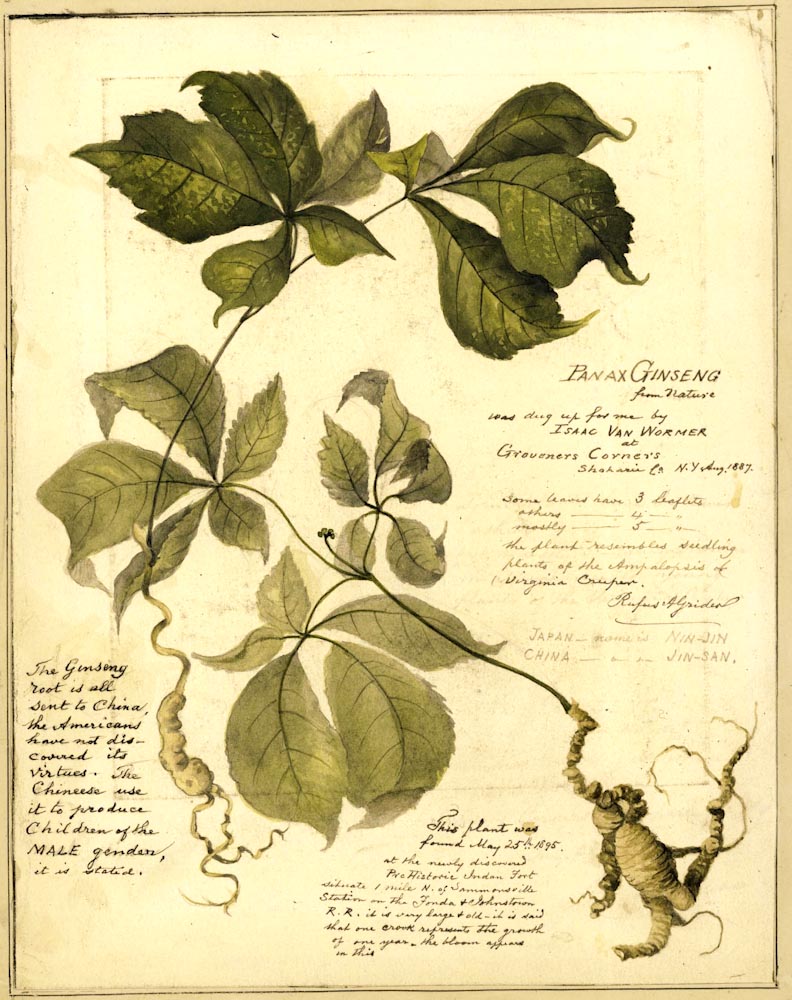

Collection VC22932; Volume 3, Item # 49.

Botanical illustrations were a common artistic theme. As usual with Grider, his is crowded with information. Besides being an artist, and amateur historian, Grider also had a strong interest in botany. Before coming to Canajoharie he had been president of the Fruit Growers of Eastern Pennsylvania.

Rufus Grider was a Moravian from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He came to Canajoharie with his two small daughters after his wife died. His day job was art teacher at the Canajoharie Academy. Susan B. Anthony also taught there but she left in 1849, 37 years before Grider arrived.

Prepared May 5, 2011 by Simon Litten, NYS DEC (retired). For questions or comments please contact Simon at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..